Introduction

It is hard to think of any person who has achieved financial security without owning at least one piece of residential property – typically the family home. Most of the people we see either own a home, are in the process of owning a home, or aspire to owning a home. This is why we make owning a family home a key aspect of our advice.

It is hard to think of any person who has achieved financial security without owning at least one piece of residential property – typically the family home. Most of the people we see either own a home, are in the process of owning a home, or aspire to owning a home. This is why we make owning a family home a key aspect of our advice.

When we see clients who already own a home, they often ask us common questions. These questions include: Should I sell my existing home? Should we renovate? Is it protected if something goes wrong (especially important for self-employed clients)? Is my home included in my will? Should it be? Should I use the home as as security for an investment loan? Should I use my home as security for my adult child’s home loan? The list goes on.

For clients who do not already own a home, some common questions include: Should I rent or buy? Should I buy something affordable for now, pay it off fast and up-grade later? Or should I buy something for more than I can comfortably afford now and simply work harder than ever before? Should I invest in shares instead, buying a fixed amount every month rather than paying off a home loan? Should I buy a business first?

These are all great questions. And we have decided to produce this ebook as a way of helping you find answers to them.

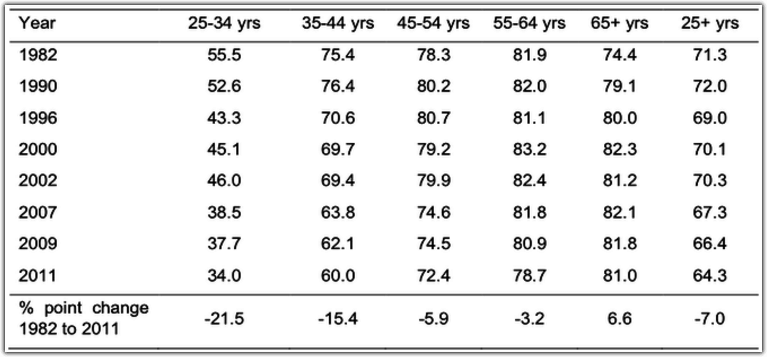

Buying a home has never been a bigger issue for many Australians. We see this in the fact that Australia’s historically high rates of home ownership are falling. Home ownership rates have fallen from 71.4% to 69.5% since the 1990s. Australia is one of only five OECD countries where home ownership rates fell during this period.

That said, you could argue that this is not actually much of a drop, particularly as the population grew strongly during this period and home prices grew even more strongly. Housing may be at a time of low affordability, but 7 out of 10 Australians still own one.

Owning a home, and variations on the theme, is typically a major point of interest amongst clients of all ages. What’s more, the home remains the greatest store of wealth for most clients. Super is catching up, and may one day overtake home ownership as the most valuable asset for most people. Certainly, some people are trying to argue this. However, it is likely that as average super balances grow average home values will also grow, due to a wealth effect between these two asset classes. That is, people will be more willing to take on larger loans to buy ‘more home’ as their super balances rise. And as older members of the community pass away, their adult children inherit their wealth, and typically use at least some of it to finance a home. Wealth in other areas of the economy always tends to find itself at least partly invested in the residential property market.

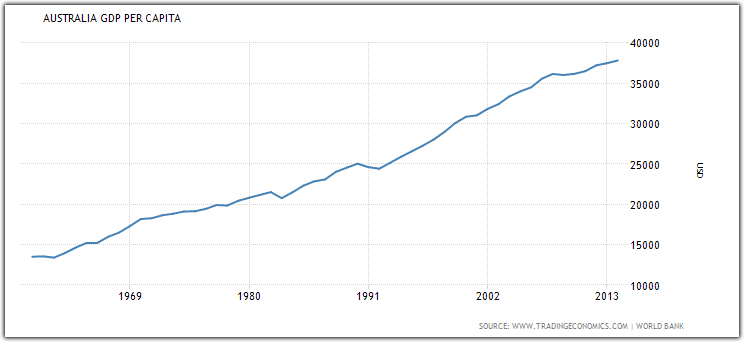

Such is the importance of the family home in people’s thinking: people feel wealthier the better their home is. As a result, if the economy keeps growing, then the value of the average home is likely to keep growing as well.

Please feel free to share this ebook with any other person who you think would find it beneficial. And, if you would like to discuss your own situation, please do not hesitate to contact us.

Chapter 1: Choosing a Family Home

Buying a family home is a unique purchase. It is the only large acquisition that we make that is one part financial and one equal part emotional. Alright, we admit it: it is perhaps two parts emotional and one part financial. And the emotional and financial elements intersect with each other, so that each individual buyer has their own list of unique personal preferences for what they are looking for in a home.

There are three main variables that impact on these personal preferences: location, features and price. Let’s look at each of these in turn.

Location

Most personal preferences start with location. People simply decide where they want to live first. Then they go looking for a specific house.

These are the common factors that dictate where people choose to live:

- Amenity (simply choosing the ‘right’ suburb is very important to many people);

- Schools;

- Transport (public and private – i.e. road transport);

- Parks and gardens;

- Shopping;

- Features such as coastline or mountains;

- Proximity to family and friends;

- Noise (eg how close a property is to a freeway or an airport flight path);

- Streetscape; and

- Proximity to work.

There is a word of caution with this last feature. Many people buy a home for its proximity to their workplace… and then change jobs. So, it pays to think not only about where a current job is located, but also where any future work might be situated. This will be easier in some occupations than in others. A police officer, for example, will have a lot of flexibility in terms of where they work. A beach lifeguard, not so much.

The Role of the Adviser

When buying a family home, there are many factors that need to be considered. Typically, a purchaser needs to ‘trade-off’ some of the factors that underpin the choice of location. Talking through these factors with a knowledgeable person can save a lot of time, money and heartache. A good adviser more than pays for themselves here.

To give but one example of such a compromise: many people seriously under-estimate the impact, both in time and money, of living a long way from where they will spend their time. Many outer suburbs, for example, require families to own two large cars as there is no other form of transport available and services are located some distance apart. Queensland’s RACQ estimate that the average weekly running costs of a medium car are at least $11,700 a year. Now, let’s say you decide to live a lifestyle that requires one car. This means choosing a location where members of the family can use public transport or walk to either work or school. This means that the family will save $11,700 each year.

At 5% interest rates, dedicating this amount to mortgage repayments would allow an extra $170,000 to be borrowed and used to buy a home. Looked at from another perspective, you could say that the price of each car is $170,000 worth of home.

Features

Circumstances dictate many of the features we need in a home. No matter how much they love each other, a family with three children simply cannot live in a one bedroom studio. A family with four car owners probably needs off-road parking. A family with large dogs needs a backyard. The list goes on.

Other situations are more unique. A person in a wheelchair, or an older person, should typically avoid second storeys, unless the house has some easily-used way of moving between floors (for example, a lift).

Other features are more a function of preference than circumstance. Some people love 100 year old Victorian-era homes. Others want their home to be as new as possible. Some people swear by brick; others prefer the aesthetic of weather board. Families with children might like zoned living, while other families find that if the home is too large everyone lives in a more isolated way than they would like.

Common features that people look for in a property include:

- Number of bedrooms;

- Number of bathrooms;

- Size and style of outdoor space;

- Size and style of indoor living space;

- Style of housing;

- Car parking;

- Swimming pools; and

- The overall ‘vibe’ of the property.

The Role of the Adviser

Once again, an experienced adviser can help clients identify the features that they need in their new home. For example, many clients will intend to buy a house to live in for the rest of their life, but not factor in that mobility might become an issue ‘down the track.’ An adviser in this situation might suggest that clients choose single storey properties that do not involve steps.

Similarly, younger clients who are yet to start a family often seriously under-estimate their residential needs after children come along. Parents of teenagers will tell you: it is not simply a case of two kids meaning you need double the space. If you want to keep liking those kids, then you need more than that!

Price

Pretty important one, this. This is the decisive factor for many people. No surprises here: the right home at the wrong price is actually the wrong home.

Pretty important one, this. This is the decisive factor for many people. No surprises here: the right home at the wrong price is actually the wrong home.

The Role of the Adviser

Working out what a client can afford is where financial advisers often make their most useful contribution. The main factors in determining how much a person can afford to spend on a home are addressed in the next sections.

Repayments

Many, if not most, people borrow at least some of the amount needed to buy a home. Repaying this loan is typically the most expensive aspect of owning the home.

ASIC provide a calculator that you can use to determine mortgage repayments for different types and amounts of loan. The calculator lets you work in two directions: you can input a given amount of money and then determine the periodic repayments for a given interest rate. Alternatively, you can determine how much you can afford as a repayment and then use the calculator to calculate the level of borrowing this repayment facilitates at a given interest rate.

It is a good to alter the interest rate payable in the calculator to determine the impact on repayments if interest rates rise. You must ensure that you can afford repayments at a higher interest rate than the one on offer, unless you know that you can fix the interest rate for the foreseeable future.

There are various ways to assess how much you can afford as a repayment. Housing affordability is often calculated by dividing the annual repayment for a loan into the annual income for the home owner. This gives a percentage: higher percentages indicate lower affordability.

For example, a potential buyer might decide that she can afford to dedicate 30% of her after-tax income to repayments. If she earns $50,000 (after-tax), this equates to $15,000. According to the calculator, on a home loan with an interest rate of 5%, she could borrow:

- $187,000 over 20 years;

- $212,000 over 25 years;

- $230,000 over 30 years.

If she increases her repayments to 35% of her after-tax salary, she can then borrow:

- $219,000 over 20 years;

- $247,000 over 25 years;

- $270,000 over 30 years.

Looked at from the other direction, a potential buyer can determine what the repayments are for a given sized loan, and then calculate the percentage of her income needed to service a loan of that size. Again, experience would suggest that you factor in an interest rate rise when deciding whether a loan is affordable.

Stamp Duty

In all Australian states and territories, stamp duty is payable on a property purchase. This can be a large expense which many first time home buyers, in particular, forget to factor in. For example, someone buying the median-priced property in Melbourne ($727,000 as of December 2015) will pay around $40,000 in stamp duty and related costs.

Happily, buyers who use debt finance are typically prompted by their lender to factor in stamp duty when they negotiate their loan agreement. Unhappy surprises on stamp duty are relatively rare.

The rate at which the duty is levied varies from place to place. www.realestate.com.au provide a stamp duty calculator which calculates the stamp duty payable in each state or territory.

Mortgage Insurance

Many lenders require borrowers to insure the lender against default. This is typically the case when the borrower borrows more than 80% of the value of the property being purchased. In such cases, there is a risk that the property could fall in value such that the full amount of the loan could not be repaid if the client sold the home.

The insurance is typically purchased at the time the mortgage is put in place. The amount of the insurance is often added to the amount borrowed, with the lender then passing the amount of the premium to the insurer. Borrowers should not be fooled by this cash flow, however: the premium is paid by the borrower, not the lender.

Premiums are typically somewhere between 1 and 3% of the amount borrowed.

Given that the mortgage insurance does not make the borrower any better off, many borrowers will seek to limit their formal borrowing to less than 80% of the value of the property. To do this, many people might source money from elsewhere (such as friends or family) in order to keep the balance of the mortgaged loan account below 80%.

Legal Fees

Purchasing a property involves some legal administration. Mortgages need to be put in place, titles need to be conveyed from the previous owner to the new one, etc. Legal fees can range up to around $2,500 for a purchase.

Council Rates

Council rates vary from area to area, but they are typically charged using a formula, meaning that the level of rates payable for a property of a given value can typically be calculated prior to purchase – or at least a very good estimate can be attained.

Insurances (Buildings and Contents)

Most home owners need to insure the building and the contents of their home. There are various online calculators that can be used to estimate these amounts. As these are all provided by commercial operators with a view to getting people to increase the sum insured, clients may do better by speaking directly with one or more insurers and obtaining a particular quote.

If you have bought a home and not yet settled, then you should look to insure the building right now. This will assist you in case anything happens to the property before you finalise the purchase. Talk to your insurer about this form of insurance.

Body Corporate Fees

Where two or more properties share some expenses of holding the properties, these expenses are typically paid by a body corporate. Body corporates tend then to charge fees to the individual landowners who make up the body corporate. Again, these fees vary according to the property, but they are typically disclosed to purchasers prior to purchase.

Useful Websites to Assist in Choosing a Family Home

There are many websites dedicated to aspects of choosing and purchasing a family home. Many of these have a vested interest and care needs to be taken. For example, websites for buyer’s advocates will tend to suggest that buying a property is too difficult for most people (and thus that they should use a buyer’s advocate). Here are some websites that offer good, objective advice.

The Hidden Costs of Buying a Home – realestate.com.au

Commonwealth Bank’s Upfront Cost Calculator – as the name suggests, this calculator gives an estimate of the costs of buying a home using debt finance.

Buying a Home – ASIC’s website for people thinking of buying a home. This is particularly designed for first home buyers.

Chapter 2: Homes as investments

The Real Estate Institute of Australia (REIA) reports that at December 1980 the median home price in Sydney was $76,000. The median home price in Melbourne was $43,000. In March 2023 the median home price in Sydney was just over $1.01 million and the median home price in Melbourne was $747,000 (source: propertyupdate.com.au). That’s a significant increase in value over nearly four decades! The increases are even bigger in the ‘better’ (ie more desired) suburbs.

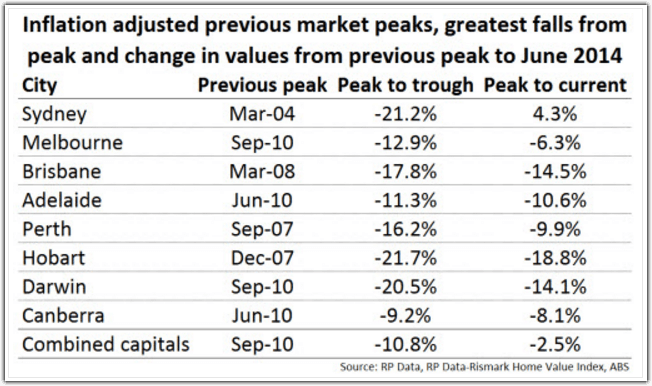

The prices in other capital cities are not as high – but the growth in prices has been pretty similar in all major cities, especially across the longer term. For example, Perth prices have actually fallen in the last three or four years – but this has followed a period before that when prices rose by more than the rest of the country.

The point is this: over the years, housing has been a good investment.

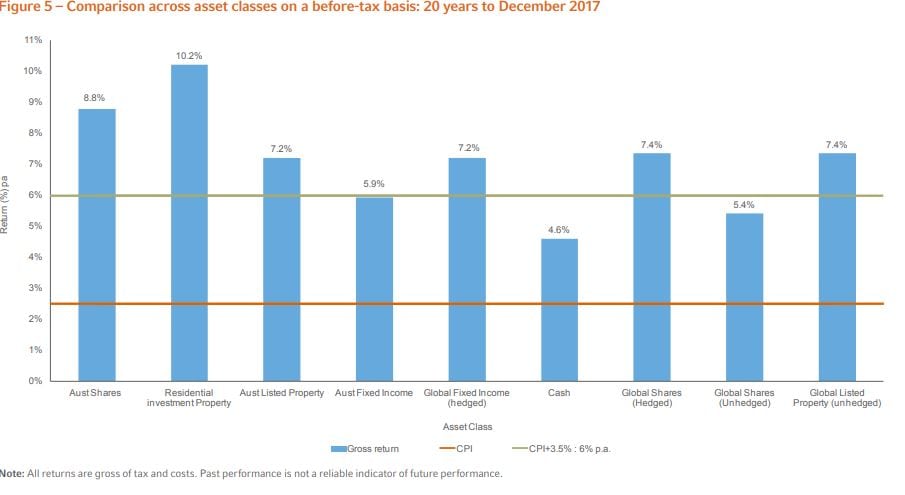

Share prices have risen a lot, too. The Russell Investments ASX 2018 Long-term Investing Report (one of the most reliable and bias-free reports available on the market) says, at page 9, figure 5, that the 20 year average for Australian shares to 31 December 2017 was 8.8%, which is only a little behind residential property at 10.2%. Here is a graph taken from that report:

Homes have definitely been good investments over the years.

Why have prices risen so much?

The media is full of theories and explanations. The best include the following elements:

- record low interest rates combined with a record 27 year period without an economic recession;

- rising international interest in Sydney and Melbourne as cities, and investment centres, connected to a (correct) perception of Australia as a safe haven. Australia is a stable political and economic environment where property rights are protected by the law;

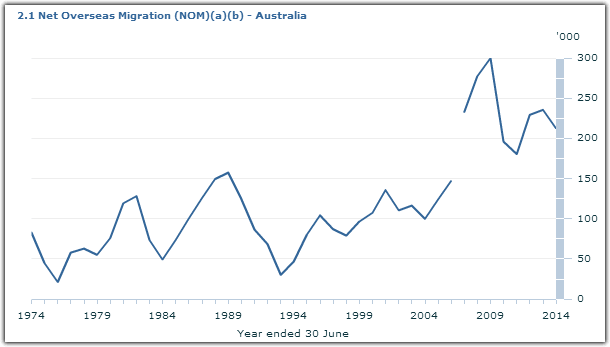

- population pressure. The national population is increasing by around 220,000 people per year. Melbourne’s population alone is increasing by more than 90,000 a year, every year. Most new arrivals are from Asia and South East Asia and are eager to enter the property market, as home owners and investors;

- negative gearing by high tax rate individuals;

- SMSF gearing;

- concerns that the share market is ‘too risky.’ Share prices fluctuate much more widely than house prices. For example, the ASX fell by more than 8% in August 2015; and

- a sense of being left behind (FOMO – fear of missing out) – prices are rising and if you do not act now you will end up paying more later.

Will this trend continue?

Home values can’t and won’t go up every year. Indeed, in the March quarter of 2018, prices fell in most capital cities. This was also true in March 2023 (source: propertyupdate.com.au).

One of the key measures of the relative value of housing is the housing affordability index. As the name suggests, as housing affordability falls, homes become less affordable. Economic theory, and economic history, both suggest that this will dampen demand for housing. Lower demand has the effect of not putting pressure on house prices, which restricts the growth in those prices, such that affordability increases. The basic point: things simply cannot stay unaffordable forever. If homes are unaffordable, people cannot buy them, and the price falls – back to where things become affordable again.

Affordability – and therefore home values – are particularly sensitive to interest rate increases. For example, if a new home owner borrows say $1,000,000 at 4% pa to buy a home, they have to pay $40,000 a year interest. If interest rates rise by say 2 percentage points to 6% pa, this increases by $20,000 a year to $60,000 a year. This interest is not tax deductible, so at the 40% tax rate they have to earn an extra $33,000 in pre-tax income just to meet the increased interest expense. (Even more when Medicare, 9.5% super, workcover and payroll tax is factored in.)

So, home values do not rise every year. That said, history shows they have risen each decade. And when you look at home values over several decades (say, 1980 to 2018) there is a significant upwards-sloping trend line.

What are future home prices expected to be?

Fifty years is a long time. But many say this is how long property should be held for. Property is an inter-generational asset (see chapter 6) and over multiple decades and generations property will typically produce excellent rates of return. Obviously precise predictions of future prices over such a long timeframe are not possible. There are too many variables in the equation. But let’s stick to the basics and look at what is expected to happen to Australia’s population over the next fifty years. This can help us then make an educated ‘guess’ about home prices.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics provides the following data (2012 is the most recent date available for this data):

| State | Population 2012 | Population 2062 | Increase % |

| Sydney | 4,700,000 | 8,500,000 | 80% |

| Melbourne | 4,200,000 | 8,600,000 | 105% |

| Perth | 1,900,000 | 5,500,000 | 187% |

| Brisbane | 2,200,000 | 4,800,000 | 118% |

| Adelaide | 1,300,000 | 1,900,000 | 46% |

| Darwin | 131,900 | 225,900 | 71% |

Income levels will rise too. Inflation runs at roughly 3% a year, as a long-term average, so a $1,000,000 home purchased in 2012 will be worth at least $4,384,000 in 2062 if it simply appreciates with inflation.

Much of Australia’s population growth is driven by immigration. More than 220,000 people arrive each year. Most are well educated, reasonably well off and aspirational: they want to get ahead in the Lucky Country and they work very hard to do so.

These aspirations are shared by older Australians too: just listen to talk back radio for a day to witness the energy and effort put in to buying and keeping a home. Over 80% of people aged over 65 own their own home – the highest rate for any age group. It’s an intrinsic part of the Australian culture and psyche, and there is often a stigma attached to not owning a home.

Obviously the more fashionable suburbs will be in more demand. They are privileged locations and people will ‘fight’ to buy there.

There is no precise formula, and it’s a very simplified model, but if you combine cultural preferences (obsessions?), dramatic population increases, privileged locations and prolonged inflation you get significant home value increases across the coming generations.

Chapter 3: Pros and cons

The above data and tables seem to be a persuasive case for home ownership. But not everyone agrees. And it is always useful to look at a contrary position. Phil Ruthven is a well-known economics and social commentator. He argues owning a home as an investment is irrational and unlikely to produce optimum investment results. He says home ownership is nice emotionally but most will be better off renting a home that suits us now and implementing a disciplined investment strategy based purely on rational grounds.

Mr Ruthven says this is particularly the case once the hidden costs of home ownership are considered, such as hours and dollars spent improving the home, rates and repairs, and stamp duty, legal fees and other transaction costs when we move every seven years.

There is some merit in what Mr Ruthven says. Especially if you move more than once every seven years or if your home is not in a well-performing suburb. In July 2014 the Reserve Bank released a report saying that house prices need to go up by more than 2.9% a year for buying to beat renting. While this report is now a few years old, the mathematics aren’t.

On balance, though, many would not agree with Mr Ruthven. Fundamentally, the great advantage of home ownership is forced savings. Apart from super most people would not save a cent without regular home loan repayments. Indeed, the forced saving of a home loan and the legislated saving of super tend to be the only ways most people save. Yes, there may be ways of managing wealth that are more financially ‘efficient’ in the pure sense of that word. But few people actually manage their wealth in these other ways. If they do not buy a home, they don’t invest elsewhere either. Over the two decades to December 2012 residential property earned 9.5% per annum. Most clients who owned properties did well and people who did not missed out. Those who own properties in the next two decades will probably do well too.

And on balance we expect the Reserve Bank’s minimum required 2.9% price increase to be easily beaten by the better suburbs in most capital cities: 2.9% is not much higher than the inflation rate, and well below the historical rates of return actually generated in these markets. If prices simply do a little better than inflation, then buying will make more sense than renting over the long-term.

What are the advantages of home ownership?

The advantages of home ownership can be as much psychological as they are financial. It’s all about the nesting instinct and territoriality: this is your home, and your home is your castle. Home ownership provides a sense of permanence and control that is important to overall psychological happiness.

Residential properties, and the loans used to buy them, are also a great way to save. Many people would not save a cent if it was not for the principal component of their home loan repayments. Later, when the home is paid off, the owners also save on rent. Loans are eventually repaid, leaving no more to pay. Rent is always due next month.

The family home, including improvements, is usually free of capital gains tax. The principal place of residence is excluded from the CGT net by dint of social policy and political survival. Improvements to the home are also CGT-free, so if a $100,000 improvement creates $150,000 of value, that extra $50,000 is tax-free. That’s why backyard blitzes are so common before people put their homes up for sale.

For older people, or other Centrelink benefit recipients, the home is outside the assets and income test for the age pension.

Increasingly older clients without significant investments are using reverse mortgages to access the equity in their home without having to sell it. Reverse mortgages turn homes into tax-free reservoirs of wealth. Individuals can smooth consumption over their expected lifespan by building up the reservoir during their working years and running it down in retirement.

The Australian Master Financial Planning Guide 2015-16 (Walters Kluwers) recognises other advantages of housing. These include:

- Providing security and stability. The alternative to home ownership, renting, may involve the owner selling the property;

- Avoiding the stigma that some feel may attach to not owning a home;

- Providing lifestyle choice even where wealth creation is not the primary objective;

- Paying off the home loan is a form of personal saving; and

- Freedom to make personal changes to the property.

What are the disadvantages of home ownership?

Property can be expensive to buy and hold. Acquisition costs include stamp duty (typically around 5% of the cost), bank fees, solicitors’ fees and titles office costs. Holding costs include council and water rates, interest, land tax, maintenance and repairs, and real estate agent’s fees. These can be significant and are often ignored when people calculate the gains made on their homes.

Critics also list the opportunity cost on foregone investments and a lack of diversification, which means higher risk. (Although, historically neither has held true. Property is a top performing asset class: the ASX-Russell Report for 2017 says property averaged 10.2% in the two decades to December 2017, just ahead of Australian shares at 8.8%, so there is no significant opportunity cost. And any historical lack of diversification has been to the homeowners’ advantage – who wants to diversify into a slightly lower-earning asset class?)

Critics say residential property is not a liquid asset. This has become less of a problem in the past 10 years because equity access loans (debt facilities linked to the value of the home) allow clients to ‘cash out’ some of the value of their home, whether for consumption, investment or business purposes.

The Australian Master Financial Planning Guide 2015-16 (Walters Kluwers) recognises other potential disadvantages as including:

- Property prices can fall, as well as rise:

- Demand for property may be lower in the future due to:

- Low inflation, which reduces the potential for high capital gains;

- Increasing unemployment rates;

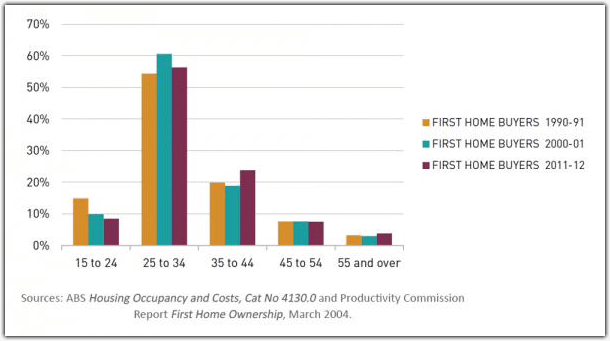

- More people deferring the purchase of the first home;

- The high costs of buying and selling property, including legal fees and stamp duty;

- The opportunity cost on missing out on other better performing investments;

- Lack of diversification;

- Property not being suited to investment;

- Miss out on other tax concessions, even though homes are CGT free; and

- Homes are illiquid, ie hard to convert to cash.

Chapter 4: Other Practical Aspects of Home Ownership

Who should own the home?

This is often a key question for self-employed clients. To them, the worst aspect of falling into financial ‘trouble’ in their business is losing the home. This causes the most angst and pain. It can even destroy marriages. Ask yourself how your partner would feel if you lost the family home as a result of your business or investment activities. It would probably rank after the death of a close relative as the worst thing that could happen to you, and the most stressful.

As a result, the question of whose name the family home should be owned in is one that all business owners or others who may be sued (health professionals, lawyers, etc) need to resolve.

Should a spouse own the family home?

If you do not own something you cannot lose it. So, for people in ‘risky’ professions who become involved in some sort of litigation, if their spouse owns the home it will typically be safe and beyond the reach of the courts in the event that professional indemnity insurance does not cover any damages claim.

The Family Law Act generally ignores nominal ownership between spouses (with some few exceptions). It generally does not matter whose name the home is in if the marriage breaks down. This applies to all the marriage assets.

So if clients are married and are considering buying a home they should think hard about whose name the house should be owned in. If one member of the couple is engaged in a risky occupation and is litigation prone, most likely it will not be in their name – unless their spouse is even more litigation prone than they are.

How do you tell who is more litigation prone? Simple. If one spouse pays more professional indemnity insurance than the other it means the actuaries think that spouse is the more vulnerable to litigation.

Our practice has access to a team of lawyers who can provide assistance on issues to do with nominal ownership of the family home. If you have any questions, please let us know.

Family trusts, family homes and the Family Law Act (“FLA”)

The Federal Court, which oversees the FLA, has sweeping powers to ignore any legal arrangements put in place to defeat the purpose of the Family Law Act. Transferring the home to a trust controlled by one party will almost certainly have no effect for FLA purposes. The Federal Court will simply ignore it. It is a powerful Court.

But owning a home in a family trust can still make sense, especially where asset protection (that is, the risk of losing valuable assets in a litigation) is an issue. Owning a home in a family trust does negate some of the tax advantages that apply to the family home. These include that a family trust cannot access the principal residence exemption, meaning that CGT is payable on 50% of any capital gain that the home enjoys. In addition, land tax can apply to family trusts.

That said, there can still be advantages for owning a home in a trust. These include:

- That the trust will outlive the current tenants of the house, allowing for inter-generational transfer of the property. Remember, the principal residence exemption is only an advantage when the property is sold;

- CGT is only paid on half the capital gain if the home is actually sold (assuming it is held for more than a year). There is an argument that homes should be owned for a minimum of 10 years, and should not be sold even if the client upgrades, but instead retained as an investment property;

- Family trusts are CGT efficient for owning appreciating assets. Beneficiaries with little or no other taxable income can receive a capital gain and pay little or no tax;

- Even if some CGT is paid, this is a small price for the security of the home being beyond the reach of litigious client, and for the tax benefits enjoyed in earlier years.

In summary, for clients who face the risk of losing the family home in litigation, family trusts are well worth considering.

As we say above, our practice has access to a team of lawyers who can provide assistance on issues to do with nominal ownership of the family home. If you have any questions, please let us know.

When should homes be sold?

In our experience, many clients are too quick to sell their homes, particularly when upgrading to a new home. If you are living in your second or subsequent owner-occupied home, ask yourself a question: do you wish you had kept the first home you bought? For most people, the answer is a resounding yes.

Homes have, on average, returned 9.5% per annum over the last two decades. When people upgrade, it’s usually not long before the sale of the old home is regretted.

People should consider never selling their old home when they up-grade, and should instead consider retaining it, renting it out and letting time do the rest. The first few months, or even years, may be tight, but before long the value of the new home and the old home will rise and the decision will be validated.

As a helpful hint, we recommend interest offset accounts as much as possible: buyers can withdraw their equity and transfer it to the new home, reducing non-deductible debt, while the old home becomes a negatively-geared investment property. If you think this could be relevant for you, please let us know.

What if your home is not expected to appreciate?

Clients in capital cities think home prices always go up. This is optimistic, but that optimism has a solid base: in most capital cities they almost always do go up. At least eventually.

But outside capital cities the position is more complex. In some places prices do not rise at all. In other places prices fall. Rural or regional clients should always consider owning at least one residential property in a capital city.

It is clients living outside of major cities who might pay the most attention to Phil Ruthven (see above). Living away from the city is often a lifestyle decision. In such cases, it makes sense to separate the lifestyle and the investment decision as Ruthven recommends. Live in the bush – but own in the city.

Homes for children

Whenever we meet with clients who are parents (and over 85% of women end up being mothers – the same proportion of men probably do as well), those children are very much in our mind.

Simply put, clients with children over the age of 18 – or at least, children now earning taxable income – should encourage those children to buy a first home, with a 20 year time frame in mind (as we say this, we are fully aware that there may be some better investments for time periods of less than ten years).

A loan, or a bank guarantee, from mum and dad means the next generation enters the property market much earlier than otherwise. This lets them buy properties at 2017 prices, rather than 2035 ones. And if the children stay at home and rent the property the tenant and the tax benefits pay much of the costs. This further accelerates the wealth creation process.

It’s a great way for clients to create a permanent financial advantage for their children. Property is an inter-generational asset. Parents and grandparents should be thinking that far ahead.

The only real down side is the risk that the property may fall in value and the parents become exposed under the guarantee. This is a manageable risk, and one most clients who are parents can easily prepare to take on.

Exercise some basic common sense and this strategy can be very low risk.

Apartments

Generally, clients should not invest in an apartment unless it is on the secondary market (ie not off the plan). We also like the apartment to have perpetual views that can never be built out, and to be one of a relatively small group. High rise is high risk.

Generally, clients should not invest in an apartment unless it is on the secondary market (ie not off the plan). We also like the apartment to have perpetual views that can never be built out, and to be one of a relatively small group. High rise is high risk.

There is an over-supply of apartments – especially high-rise ones – in most capital cities so the capital gain prospects just aren’t there. Sure, some apartments will be OK investments. But many won’t be. It’s generally better to be safe than sorry.

In 2018, the ABC reported on substantial falls in apartment prices in Brisbane, while Business Insider was reporting that this was a common experience in all capital cities.

Tourist accommodation

We are not very happy with investments in ‘tourist accommodation’ either. There is an over-supply and the capital gain prospects just aren’t there.

Think about this real-life example. It was reported that in 2011 a client made the classic mistake of not getting advice before they bought a Gold Coast apartment for $400,000. They bought it while they were on holidays. It seemed a good idea at the time. The rent was good, $30,000 a year, which meant the interest of $22,000 a year looked like it would be more than covered. The problem was management fees of $15,000 a year and cleaning costs of $6,000 a year. Throw in rates and water and the total outgoings became more than $45,000 a year. The cash shortfall was $15,000 a year.

The apartment is worth less now than it was in 2011. Brand new apartment blocks are springing up all the time. This apartment is not new anymore and so it struggles to compete with those that are new. What’s more, holiday renters can treat a property roughly. Any capital gain is decades away.

Holding costs of $15,000 a year means the family’s own week in Surfers Paradise each May costs more than $2,000 a day. That’s what we call an expensive holiday.

In summary, tourist accommodation is too risky. There are too many apartments and too few genuine buyers, and ‘owners’ are at the mercy of the apartment managers.

Chapter 5: Gender and Home Ownership

Introduction

In this chapter, we want to discuss some important elements of home ownership from the point of view of women. It can be hard to get a completely accurate picture of the situation regarding women and home ownership. Doing so involves gathering data from various sources, all of which are reputable but some of which contradict or at least disagree with each other. In this chapter, we make our best attempt to examine the ‘state of play’ for women and, in doing so, we identify a particular group – single mothers – who report much lower levels of home ownership than either coupled women or single women without children.

Please note: In describing the situation for women and home ownership, we are aware that there are also many men – for example, single fathers – who face many of the same difficulties as women when it comes to home ownership. Those men would benefit from reading these materials as well.

However, we have prepared these specific materials as part of our commitment to addressing gender inequity in financial planning. For that reason, and that reason only, this article is largely written from the perspective of female clients. Men in similar circumstances are encouraged to make use of this chapter as well.

General Overview

The Good News

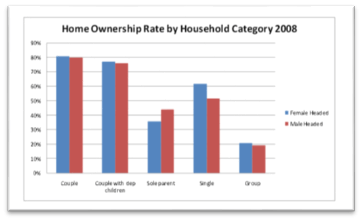

80% of women living in a couple but without children own their own home. (In this article, the term ‘homeowner’ includes someone who is repaying a home loan as well as people who own their home outright). Around 76% percent of women living as a couple with children own their own home. Unsurprisingly, the figures for men are essentially the same. Women living as part of a couple have high rates of home ownership. In terms of gender inequality and home ownership, then, the issue is really what happens to women who are single. We discuss that in following sections.

When it comes to gender equity and home ownership, there is actually some good news to be reported. To begin with, in its most recent data, which dates from 2011-12, the ABS reports that 59.6% of females aged over 15 own their own dwelling (with or without a mortgage). This compares to 55.9% of males.

The data excludes dependant students aged between 15 and 24. It therefore includes younger people who are not studying but do not live independently. Thus, these figures probably under-estimate the actual rate of home ownership for adult men and women.

The figures reflect a broader phenomenon of young women being more likely to live away from their parents than young men. According to research conducted by the University of Melbourne, for example, 24% of men aged 26 to 29 still live with a parent, compared to just 14.7% of women of that age. A similar differential exists in younger age groups, albeit with fewer younger people living out of the family home. That said, the researchers also suggest that the difference in the age at which men and women leave home is attributable to the fact that women tend to take on a partner at a younger age.

An aside

Interestingly, the same research also suggests that deferring leaving the family home beyond the age of 24 has a negative impact on wealth creation. The best time to have left home, in terms of achieving wealth by mid-life, was between 21 and 24. This would seem to suggest that staying at home long enough to become vocationally-qualified, but not much longer, is a good idea.

The Not-So-Good News – General Wealth and Income Levels for Women

In terms of gender equality, the good news might end there. The same report also observes that the average single man has 23% more asset wealth than the average single woman. Given that the family home is the single largest asset owned by the average Australian household, accounting for 43% of total household wealth, this lower level of assets for women must reflect lower levels of residential property-based wealth for women.

This is the case with wealth in general. When it comes to income, the situation is just as clear. According to the Workplace Gender Equality Authority, average full time earnings for women are 17.9% less than they are for men. The pay gaps vary from industry to industry, with the largest gap (30.5%) identified in the financial and insurance services industry. This industry is the third-highest paid in Australia, behind only the mining industry and the professional, scientific and technical services. The average difference in the mining industry was 19.6% – slightly above the national average. The difference in the professional, scientific and technical services industries was 24.4%.

So, the three highest-paid industries in Australia have gender salary differences that exceed the national average. There are no industries in which a pay gap is not observed – and remember, this is for full time earnings. At the ‘bottom’ end of the well-paid scale is the food and accommodation industry. This is the lowest paid industry in Australia. The gender gap here is also the lowest, at 7%. The next poorest-paid profession is retail, with a gender gap of 14%.

The Specific Situation for Housing and Women

When it comes to identifying specific issues for women and home ownership, one difficulty is the fact that many people buy homes as couples. It can therefore be difficult to properly gauge the home ownership situation for all women, given that many are living in couple relationships. And, as stated above, the rate of home ownership for women and men living in couples is quite high – over 76% for couples with children and over 80% for couples without children.

And we know that, in general, almost 60% of women own their own home – a higher overall rate than for men. The incidence of same-sex couples is very low, so the data must mean that single women, in general, own property in higher proportions than do men. But when we examine the data more closely, we find significant variations in the rate of home ownership for single women – and these differences are very important to us as financial advisers who genuinely want to address issues of gender inequality. Let’s discuss some of the conclusions that can be drawn from this examination.

Conclusion 1 – kids are expensive and make owning homes more difficult

In 2012, three South Australian researchers (Kupke, Rossini and Yim) examined the issue of home ownership for women. Their research revealed a substantial amount of useful information, including the following:

- 36% of single mothers achieve home ownership;

- 44% of single fathers achieve home ownership;

- 62% of single women without children own their own home;

- Over 80% of couples without children own their own home;

- Over 75% of couples with dependent children own their own home;

- 52% of single men without children own their own home; and

- 5% of sole parent households are led by a woman.

Single parent families (described as ‘single mothers’ and ‘single fathers’ above) are those within which a child spends more than 65% of his or her time with that parent. By contrast, shared care is where the children spend more than 35% of their time with each parent (or no more than 65% of their time with one parent).

Single parent families account for somewhere around 77% of all families in which the parents are separated (we have to say ‘around’ because the AIFS data is now somewhat dated). Given that 88.5% of single parents households include a single mother, this means that around 67% of all separations result in single mother households whereby the mother provides at least 65% of the child care.

The following graph shows the rates of ownership for each type of household.

(Source: Identifying Home Ownership Rates for Female Households in Australia, Kupke, Rossini and Yam, 2012).

Taken altogether, the impact of the data is clear: single parents (male or female) have a harder time owning their own home. Separating after becoming a parent, or not having been a member of a couple in the first place, reduces the rate of home ownership by more than half for a woman (75% down to 36%), and 40% for men (75% down to 44%).

Looked at from another perspective, the likelihood that a single man will have a home drops from 52% to 44% (which is actually a drop of 15% from the non-parent rate of 52%) if that man is also a single parent. For a woman, the likelihood drops from 62% to 36% (a 40% drop).

So, being a sole parent significantly limits a person’s ability to own a home. Because single parents are more likely to be women, this limitation impacts women more than it does men.

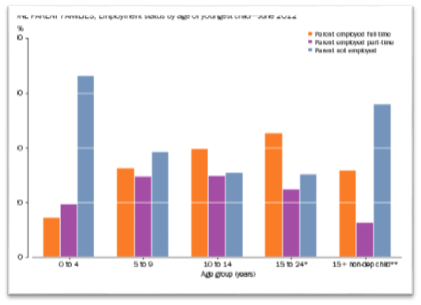

The ABS also tells us that 15% of all families are single parent families, and that fewer than 30% of single parents with at least one child aged four or under have paid work outside the home. This figure increases as children age, but fewer than 40% of single parents with at least one child aged under 15 are in full-time employment. Graphically, the situation is as follows:

(Source: ABS 6224.0.55.001, June 2012).

So, we can see that single parenthood seriously compromises a woman’s ability to own her own home. A single mum is 40% less likely to own a home than a single woman without children, and less than half as likely to own a home as a woman living as a member of a couple.

The data also tells us why: by the time their youngest child is 15, less than 50% of single parents are employed in full-time work. This leaves single parents with much lower incomes with which to raise their family – and less scope therefore to invest in their own home. And given that women are eight times more likely to be single parents, this effect impacts on women more than it impacts men.

This is consistent with the next conclusion that can be drawn from the data.

Conclusion 2 – there is home ownership… and there is home ownership

The above data looks at overall rates of home ownership. Kupke et al also looked at the type of housing that different groups own. 38.7% of the housing owned by single mothers, and 35.9% of the housing owned by single fathers, was designated as ‘cheap’ housing. This was housing in the first quintile (ie the bottom 20%) in terms of property price.

For the cheapest housing, there is little difference between single mothers and single fathers. However, a further 25% of housing owned by single mothers came from the second quintile, compared to just 6.2% for housing owned by men. This means that 64% of the homes owned by single mothers are in the cheapest 40% of homes. Only 42% of single fathers own homes in this cheapest 40%.

At the other end of the scale, 23.8% of single fathers who own homes own homes in the top quintile in terms of price, compared to just 7.1% of single mothers. When we combine these figures with the general rates of home ownership for single parents, we see that just 2.5% of single mothers own homes in the most expensive quintile (7.1% of 36%), compared to 10.4% of single fathers.

That is, a single father is four times more likely to own an expensive home than a single mother.

Conclusion 3 – women actually buy homes more readily than men

Kupke et al also note that, as might be expected, the proportion of male and female headed households who own their own homes are very similar when men and women live in male-female couples, either with or without children. (Unfortunately, the researchers do not reveal how they define a male-female household to be headed by one or the other member). But in terms of gender and the family home, this does not really matter. Women and men who live together have very similar (and high) rates of home ownership.

So, partnered men own homes at the same rate as their partners, but single men own homes at a lower rate. And we know that single mothers have lower home ownership rates than single women generally. This means that it is single women without children who most readily buy homes – and that one of the benefits that men gain when they partner with a woman is an increase in home ownership.

The ABS reports that the family home is the single largest asset owned by the average Australian household. It accounts for 43% of total household wealth. There is an obvious implication here: when men get a partner, they become more likely to buy an asset which will go on to represent almost half of their wealth. Partnership with a woman makes men wealthier.

This finding might well be related to the frequently-observed fact that married men live longer than single men. The reasons for this increased longevity include that coupled men eat more healthily, are more likely to identify and address health complaints and experience less stress. To that we can add that coupled men are wealthier than single men.

As a general proposition, partnering with a woman seems a very good idea for men. They become healthier and they also become more likely to own a home, which means they become wealthier too.

Conclusion 4 – lower incomes make for lower home ownership.

Finally, the data on full-time earnings points to a general situation for women. On an hourly basis, they are paid less than men. In addition, pregnancy and its aftermath typically mean time out of the (paid) workforce, with the ABS reporting that mothers provide just over twice as much child care as fathers. The average is over 8 hours per day – more than a third of all time and around half of all waking hours.

While the data does not show it, presumably the amount of hours spent on child care for single fathers is as high as for single mothers. Looking after kids is time consuming and makes paid work less possible.

What’s more, because single mothers are eight times more common than single fathers, the fact that single fathers face much the same difficulties as single mothers does not change the fact that women on average do more of the child care.

This leads to a ‘double whammy’ for single mothers: they get paid less per hour on average and they have fewer hours available to work.

Summary of Home Ownership and Women

In summary, we can say the following:

- Women earn less than men;

- Notwithstanding this, women are more likely than men to buy property;

- Couples have high rates of homeownership;

- Upon separation, 2/3rds of women end up as the main carer (the ‘single parent’) for their children;

- Single parents have much lowered rates of home ownership (36% for women, 44% for men); and

- Single mothers who do own homes own cheaper homes.

So, while women generally do well regarding home ownership, single mothers experience substantial inequality when it comes to home ownership (although single fathers do it tough, as well).

The following section contains some financial planning strategies that can be implemented to try to reduce the impact of this disadvantage.

Strategic Financial Planning Responses to Gender Equality and Home Ownership

So, what can a person faced with this inequality do?

All strategies must start from a simple point: women are actually more predisposed to buying their own homes. However, this tendency is hampered by one or more of three common factors. These are:

- the fact that women earn less in general for the average hour worked;

- the fact that mothers have (on average!) fewer hours available for paid work; and

- the fact that the financial burden of raising children, where it is not shared between parents equally, falls more on women than on men. Children are expensive.

These factors are cultural as much as anything. This complicates financial planning because it means that women must often respond to things that are largely outside of their control. Nevertheless, there is much worth considering. The two broad strategies are:

Anything realistic that increases income. We emphasise realism here, particularly because of the demands of child care. Once kids have arrived, it is no longer a simple matter of increasing the hours of paid work, or undertaking time-consuming study to qualify for a better job. Kids make these difficult, if not impossible (although, if possible, they should be pursued). Common strategies include:

- Changing jobs;

- Asking for a raise;

- Organising child care that facilitates increased work hours, with the income being dedicated to buying a home;

- Organising time at work such that more hours can be worked in a given period of time (for example, minimising lunch breaks, or extending hours on four days a week and allowing for a day off (from the paid job – the kids will still be there!) on the fifth. This increases income for a given amount of time and travel cost;

- Working from home at least some of the time;

- Buying an investment property that generates net rent (often achievable if some form of property settlement has been reached);

- Taking in a paying housemate (be careful – it is your kids’ home as well); or

- Working for yourself (in a manner that suits you and in an industry where the business will succeed).

In reviewing the above, the striking thing is how much easier it is to increase income when trade or professionally-employed. Trade and/or professional work is typically more portable, both in terms of the time of day when it occurs and where it can be done. A retail worker, for example, has to be in the shop when the shop is open. She has no choice over time or place. An accountant, by contrast, may be able to work from home and/or at night.

So, women (at any time of life) moving towards professional work is likely to be a good move – but again, only if it is realistic. The best time to train is before you need the increased income – before the kids arrive. Once you have become a single mother, it might be too late.

Anything realistic that decreases expenses. Again, the emphasis is on realism, because much of the expense of child-rearing is unavoidable. The 2012 NATSEM report on the cost of raising children found that transport and food are the two main expenses across a child’s life – hardly fertile ground for significant cost-cutting.

But the standard financial planning areas of debt management, cost reduction and tax optimisation may all feature as ways to ensure that those costs that can be minimised are.

Chapter 6: Retirement and the Family Home

The family home is a residential property. But it is also a financial asset. In fact, 43% of household wealth is contained in family homes. What’s more, the twenty-year average return on residential Australian property to 31 December 2017 was 10.2%. The average age of retirement for a man is 63 years and for a woman is 59 years. The life expectancy for anyone who reaches the age of 65 is 84 for men and 86 for women. This means that the average duration of retirement is well over 20 years – a period over which the value of the home has historically tripled. So, the family home remains a very important asset in retirement.

Financial Planning, Retirement and the Family Home

One of the key benefits of a family home is that its value is exempt from calculations used to determine Centrelink aged pension benefits. In addition, if and when an owner needs to move into an aged care facility, only a portion of the family home is counted in the assets test used to calculate the means tested components of the accommodation and care costs.

This is usually a good reason for older people to retain the family home, even beyond the point when they move into aged care.

That said, family homes are relatively large, single assets with a particular feature: they do not produce income (although they do remove the need to pay rent, which is an income-like benefit). It is this income feature (or lack of income feature) that is often the most pressing issue to be addressed when it comes to home ownership.

The Best of Both Worlds – Asset-Rich and Cash-Rich

In the perfect retirement world, the lack of income generated from family homes does not matter. Other elements of the financial profile, and in particular superannuation, can be used to finance day to day expenditure. The family home sits neatly within a broader financial profile, providing housing for minimal outlay and continuing to provide substantial capital growth in the most tax-advantaged way.

In this world, the client is able to retain their family home throughout their retirement.

A Common Dilemma – Asset-Rich, Cash-Poor

Unfortunately, not everybody has done this well. Many people own their family home and not much else. This can lead to a common retirement problem of being ‘asset-rich but cash poor.’ For some people, this situation can lead them to consider ‘downsizing’ the family home, whereby they sell their current home and then buy another home for some smaller value. This frees up cash to finance lifestyle.

Sometimes, downsizing works well. For example, where the new home entails lower maintenance or is better located, the retiree gains a double benefit: they have more money to spend and a preferred place to live.

But if done for purely economic reasons, downsizing should be seen almost as a last resort when it comes to funding a retirement. In this following section, we examine various benefits of downsizing. Before we do that, however, let’s examine the inherent risks in downsizing.

The Risks of Downsizing

While the lure of increased spending money can encourage people towards downsizing, downsizing is not without its risks. These risks include the following:

High Transfer Costs. Depending on which state you live in, the costs of selling one home and buying another are substantial. For example, selling a property in Victoria for $600,000 will cost between $12,000 and $18,000 in agent’s fees (source: Choice magazine). Purchasing a new property for $400,000 will lead to $19,000 in stamp duty (source: State Revenue Office). Add in another $3,000 or so in costs (legal, removalists, etc) and the changeover cost will be somewhere between $34,000 and $40,000). So, selling one home for $600,000 and buying another for $400,000 does not give rise to actually receiving an extra $200,000 in cash. The cash benefit is no more than $166,000.

The ‘cheaper’ house may not be cheaper. When downsizing, most people are moving from a house they know well to one that they do not know at all. This can lead people to experience unexpected costs that seriously eat into any money that has been ‘freed up’ by the move. These costs can include unknown faults that need to be rectified, or just simple modifications to bring the home up to a standard that the new residents enjoy.

The home is an exempt asset for Centrelink purposes. Cash is not. So, unless the amount of freed-up cash is less than the threshold, there will be a change to the asset-tested Centrelink pension amount. Swapping house for cash can reduce pensions.

Reduced Future Capital Growth. The twenty-year average return on residential Australian property to 31 December 2017 was 10.2%. The example change, above, from a $600,000 home to a $400,000 home, would have therefore ‘cost’ almost $20,000 a year in lost capital growth (9.8% of $200,000).

As capital growth is a percentage, it follows that reducing the value of the residential property being held will reduce any future capital growth that will be available. The average age of retirement for a man is 63 years and for a woman is 59 years. The life expectancy for anyone who reaches the age of 65 is 84 for men and 86 for women. This means that there is a good chance that a women retiring at 59 faces another 27 years (on average) in which to finance her retirement. Imagine the negative effect of downsizing on capital growth extrapolated out over 27 years.

Because retirements can be long, the early years of retirement, in particular, are years in which it is most beneficial that a person try to continue to accumulate as much wealth as possible. Downsizing early in retirement can make the later stages of retirement difficult.

If the new home is cheaper, there may be a reason. Amongst other things, the price of homes tends to be a function of demand. So, if the new home is cheaper, this is because fewer people want to buy it. The client needs to ask why this is the case. Is the new home further from amenities, such as shops and, importantly, health care? (Retirement does have an inevitable conclusion, after all).

It is not unusual to observe people moving to a cheaper area earlier in retirement, only to find themselves unable to afford to move back to their original area years later when health or family needs make the new home no longer appropriate. This can be a particular problem for sea or tree changers.

Of course, the new home might also simply be cheaper because it is not as good as the old one.

Moving out of the current area can have unexpected consequences. Many people find that moving to a new area is not as easy as they expected it would be. One relatively common tale is where a couple move in retirement, only for one of them to die sooner than expected. This then leaves the surviving member of the couple living some distance from friends and family and finding it difficult to make new friends in the new location. Widows, in particular, often tell the tale of no longer being invited to socialise after their husband has passed away.

Alternatives to Downsizing

The appeal of downsizing lies in the cash that it frees up. This cash can then be used to finance retirement activities. It follows, then, that other strategies that make spending money available to a retiree should be considered as alternatives to downsizing. Potential strategies include (the links open up to substantial discussions about each strategy):

- Working longer (ie deferring retirement, using a transition to retirement pension or retiring gradually);

- Working longer AND superannuating heavily;

- Reverse mortgages;

- Centrelink’s Pension Loan Scheme (a scheme that is available to people receiving something less than the full aged pension);

- Home reversion strategies;

- Inviting in a housemate with whom to share costs;

- Reducing costs, such as car costs (NB: car costs can increase after downsizing if the new area is not close to amenities or public transport); and/or

- Renting out the current home and then renting a cheaper home yourself, using the difference to finance lifestyle (this will affect the income test, but will preserve the higher asset base). This solution can often be the best one for people contemplating a seachange or treechange, where they are moving to an umfamiliar area. Even spending a year or two renting, while you check out the new area to see if you really do want to live there long-term, can be a really good move.

Estate Planning and Inter-Generational Planning

As outlined above, recent experience has been that median house prices have tripled over the average 20 year plus retirement. This means that retaining the family home has a substantial impact on both estate planning and inter-generational financial planning. Put very bluntly, the more home a retiree owns, the greater the amount that can be distributed to their estate when they die.

Similarly, a retiree who owns a home is typically in a better place to provide assistance to younger generations who might need it. It is easier, for example, for a person with substantial real estate assets to offer a guarantee of a child’s loan.

Chapter 7: Inter-generational financial planning and the family home

As the name suggests, inter-generational financial planning (‘IFP’) aims to treat a family as what it usually really is – a single vertically-integrated economic unit. Most people think across the generations when it comes to their wealth management – and so as financial advisers we do too.

This is particularly the case when it comes to homes. Homes account for 43% of Australian household wealth. What’s more, around 70% of Australians live in a home they own themselves (with or without a mortgage). Put simply, homes are critical to the financial aspirations of most people.We see all clients as potential candidates for IFP. We always try to spend a little extra time with all new clients, during which we find out a bit more about the person, their life views and their relationships with friends and family. The purpose is not completely social. Often the extra time reveals important facts, hopes and attitudes that can then be blended into our advice and strategies, making them better than ever.

The Family Home and Retirement Planning

One of the key benefits of a family home is that its value is exempt from calculations used to determine Centrelink aged pension benefits. In addition, if and when an owner needs to move into an aged care facility, only a portion of the family home is counted in the assets test used to calculate the means-tested components of the accommodation and care costs.

This is often a good reason for older people to retain the family home, even beyond the point when they move into aged care.

Inheritances

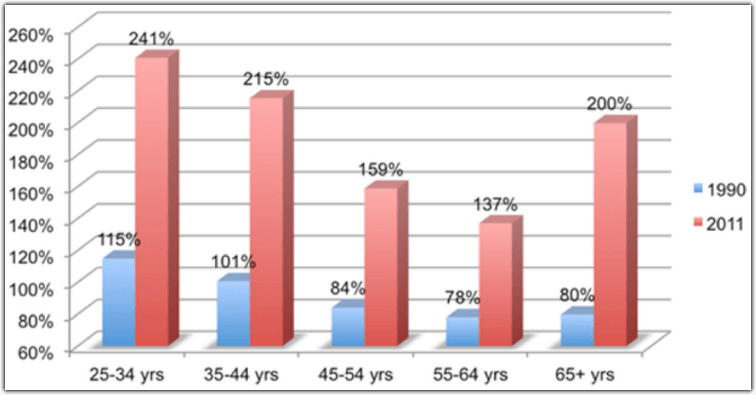

In December 2014, the Grattan Institute published ‘The Wealth of Generations.’ The research paper can be viewed here. The report contains some very significant findings, including the observation that the wealth of Australians aged between 65 and 74 increased by an average of $200,000 in the eight years to 2014. The wealth of Australians aged between 25 and 34 decreased on average over the same period. This increase was entirely due to the fact that older Australians were more likely to own homes, and more likely to own those homes outright, then their younger counterparts.

Amongst other things, this tells us that there is about to be a very significant transfer of wealth from older Australians to their younger children and grandchildren.

Inheritances upon death – estate planning and the family home.

The first thing to note is that not all family homes are included in a deceased’s estate. The entity that is ‘the family’ is not a legal person. Therefore, ‘the family’ cannot own an asset. Instead, individual members of a family own the home under some form of co-ownership. By far the most common such form is joint tenancy. Joint tenancy is subject to the principle of survivorship, whereby the remaining joint tenants automatically acquire a deceased person’s share of a property upon death. There is nothing left to the estate of the deceased. It is only when there is one surviving owner, at which point the property ceases to be a joint tenancy, that estate planning for the property becomes an issue.

Where a couple own a home as joint tenants, the home will eventually form part of the estate of the second member of the couple to die. This means that most wills for home-owning couples will still contemplate the family home as an asset, if only in the event that the willmaker is predeceased by their partner.

If that sounds complicated, let us explain. It is very common for a married couple to own a home together as joint tenants. If one member of the couple die, for example, the husband, then the wife does not ‘inherit’ her husband’s share of the home. Instead, her husband’s ‘share’ of the house is basically cancelled and the wife is then left as the only surviving owner. It is only when the wife dies that the property will be inherited – and it will be inherited according to her will, not his.

Capital Gains Tax

Provided that the home was the principal place of residence for deceased person, there is no CGT payable upon the transfer of a property following death. This is the case whether title to the property is transferred to the deceased’s beneficiaries or is sold to a third party.

The principal place of residence exemption extends for 6 years after a person vacates a property, provided that they do not claim any other property as the principal place of residence during that period. This means that a family home that was owned by someone who spent up to the last six years of their life living elsewhere, such as with relatives or in care, can usually retain its CGT exempt status.

Targeting the Inheritance

Sometimes, clients will seek to target particular assets to particular beneficiaries in their will. A common example is where there is an adult child who is disabled and continues to live with their parents into adulthood. In these cases, many parents leave the home to that child, and leave other assets (such as investment assets) to their other beneficiaries.

This targeting it one way in which financial planning can extend beyond generations.

What to do with the Inheritance?

Once a home has become the subject of a will, ultimately it can be either sold or kept. If kept, it can be used either as a place for the beneficiaries to live or held as an investment. If it is lived in by a beneficiary, then it may become their principal place of residence, in which case it will retain its CGT exempt status into the future.

If the family home is a representative residential property (by which we mean it is likely to achieve the average rate of return for residential property) then retaining it as an investment is often a good financial move. The twenty-year average return on residential Australian property to 31 December 2017 was 10.2%. This return slightly exceeded that for Australian equities over the same period.

Whether a home is kept often depends on the number of beneficiaries who are to share it. As would be expected, where multiple beneficiaries are entitled to a share of the property, it is typically harder to keep the property. The beneficiaries would need to agree to become co-owners, which would in turn require that they each have similar personal financial situations.

Keeping the home is more common where there are fewer beneficiaries. If there is only one beneficiary, then he or she simply makes up their own mind as to whether to keep the property. Where there a few beneficiaries, they may decide to own the property as co-owners. Or, one common alternative is for one beneficiary to ‘buy out’ one or more of the other beneficiaries. This is discussed in this article by Di Rosa Lawyers, in Adelaide.

Timing the Inheritance

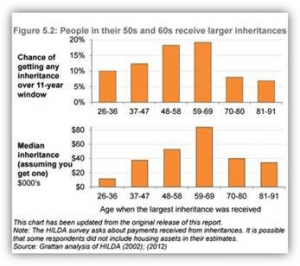

Most inheritances are received relatively later in the recipient’s life. The report by the Grattan Institute includes the following graph:

What the graphs show is that a person’s prospects of receiving an inheritance peak in that person’s 50s and 60s. What’s more, if the inheritance is delayed until later in life, it is larger. That is, the relatively few younger people who receive an inheritance receive smaller inheritances.

This would seem to reflect the fact that most people inherit from their parents, which is happening quite late in the inheritors’ life as their parents live into their 80s and 90s. (We expect that the more than 5% of inheritors who receive inheritances in their 80s receive them from age-peers such as siblings, or even adult children, rather than parents).

Assistance Buying Homes That Doesn’t Involve Inheritances

Assisting Younger Generations to Buy a Family Home (or a Better Family Home)

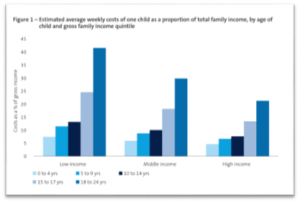

As the above graph makes clear, most inheritances occur after the recipient turns 48. By that age, the recipient is already well into their own peak cost years – the years when they are raising children. The following graph comes from the University of Canberra’s National Centre for Social and economic Modelling’s (NATSEM) 2013 report, ‘The Cost of Raising Children in Australia.’

As this graph shows, the proportion of household income that is spent on children is high throughout their life, peaking once they turn 18. Unfortunately, inheritances, when they come at all, usually come after the kids have been raised.

How handy would an inheritance be if it was received earlier in the recipient’s life – when they most need it, but before their benefactor actually dies?

For this reason, increasingly, older clients are looking for ways to assist adult children to buy their own home while the older client is still on the planet. Ways to do this include:

- Buying a home in conjunction with a child;

- Guaranteeing a loan to assist a child to buy his or her own home;

- Utilising multiple interest offset accounts such that the older client’s savings can offset the younger person’s mortgage;

- The older client gifting some money to the adult child; or

- The older client making a soft loan to the adult child.

Assisting Older Generations to Buy a Family Home (or a Better Family Home)

Sometimes, it is the younger generation that is in a position to help the older generations buy homes. This is often the case where the older generations were the original immigrants to Australia, for example, and arrived with limited employment prospects. The children of immigrants have long been over-represented among the ranks of academic achievers, and this correlates with higher earnings for those children.

In these situations, many of the techniques commonly associated with older clients helping their children can simply be reversed. A younger client might co-own a home with his or her parents, for example. Or, a young person might use their savings to offset a mortgage for their parents.

For higher tax-paying younger clients, the tax advantaged nature of the family home can be of assistance. If the home is wholly-owned by their older relative, with the younger client then to inherit it when their parent or grandparent dies, then there will be no capital gains tax payable when this happens. (Against that is the obvious fact that interest on any money borrowed to finance the purchase is not deductible along the way).

The Importance of Written Agreements

While most people consider their family to be a single economic unit, the law does not. For that reason, transfers of wealth between generations should usually be supported by written agreements between the participants. This can often be overlooked – especially for social reasons. One very common observation is a son-in-law refusing to sign an agreement that says he must repay money that is lent by his wife’s parents.

Persistence is necessary, though, because the absence of a written agreement can mean that the initial intention of the strategy is not met. For example, if a client gives money to another person to be used towards buying a home, then that money becomes the property of that other person. If this other person is married, for example, then the money actually becomes part of the assets of the marriage – and can be distributed accordingly if the marriage ends.

As Ian McLeod of RP Emery puts it:

Verbal agreements are notoriously difficult to prove which makes the enforcement of a verbal agreement time consuming and challenging. Not only do you need to prove the verbal agreement exists (and each of the criterion set out above), but you also need to evidence just what the actual terms of the agreement are, which, in the absence of written documentary evidence, can boil down to one person’s word against the other.

Superannuation and Family Homes

Very commonly, the main focus of IGFP is to provide housing for the younger generations – at least, housing that is within a sensible distance of where Grandma and Grandpa are living.

Accordingly, it pays to remember that, ultimately, private housing must be bought using after-tax dollars. The deposit used to purchase a private residence, for example, must be saved after tax is paid on the purchaser’s income. The principal and interest payments on the loan must also be paid out of after-tax income. Ultimately, the whole property is paid for after-tax.

As a result, it becomes clear that, where the tax payable on income is lower, it will require less pre-tax income to buy the same amount of house. The following table shows how much pre-tax income is required to buy a $500,000 property for various marginal tax rates.

| Tax Rate | Pre-Tax Amount Required | Tax Paid | Amount Remaining |

| 0% | $500,000 | 0 | $500,000 |

| 15% | $588,235 | $88,235 | $500,000 |

| 19% | $617,284 | $117,284 | $500,000 |

| 32.5% | $740,741 | $240,741 | $500,000 |

| 37% | $793,651 | $293,651 | $500,000 |

| 45% | $909,091 | $409,091 | $500,000 |